This is a guest post from Trisha White at the National Wildlife Federation.

Thanks to smartphones and applications (apps), we can easily swipe and tap for everything we need right from the comfort of our couch and have it delivered to our door. From food to friends to fantasy vacations, we humans now have it all at our fingertips.

But wildlife can’t be slackers–no one delivers to a nest or den.

- Turtles don’t have Tinder to find mates, they have to travel to breeding areas.

- Deer can’t use Doordash when they get hungry, they have to forage for food.

- Opossum don’t have Priceline to help them get away from predators.

- Armadillo can’t use Zillow to find a new home, they have to search for territory.

- Foxes can’t Facetime when they want to communicate with family, they have to find them.

To get what they need to survive and thrive, animals need to leave home and move around their habitat to meet their daily and lifetime needs. And too often that travel puts them in harm’s way.

On the Move

Wildlife move in daily, seasonal, annual, and lifetime cycles. Within a single day, they may only leave home to find food. Seasonally, wildlife move to adapt to changes in weather. And over the course of a lifetime, animals move extensively throughout their habitat for the many stages of life.

Some animals spend their entire life in a small area, while others may travel hundreds of miles a year. For example, an urban squirrel may find all the food, nesting material, and mates they need within a single city block. Alternatively, some pronghorn travel 300 miles roundtrip each year to follow available vegetation.

For wide ranging species like the pronghorn, getting from point A to point B and back often means having to navigate over several dangerous roads and highways. More than four million miles of concrete criss-cross the U.S. Our impressive infrastructure makes it easy for us to get around, but creates a deadly gauntlet for wildlife. In fact, an estimated 1-2 million large animals are killed by motorists every year; one animal every 26 seconds.

Wildlife Bridges

Not as easy as getting a Lyft, but innovative solutions for restoring wildlife movement have emerged over the last three decades. Wildlife biologists teamed up with highway engineers to design/build/create wildlife crossings to allow animals to cross over or under roadways, never having to enter the right-of-way. Wildlife crossings include bridges, enlarged culverts, and tunnels combined with fencing along roads to funnel animals to the crossings. These structures have proven to be the most effective measure to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. Some examples of successful wildlife crossing projects in the United States include:

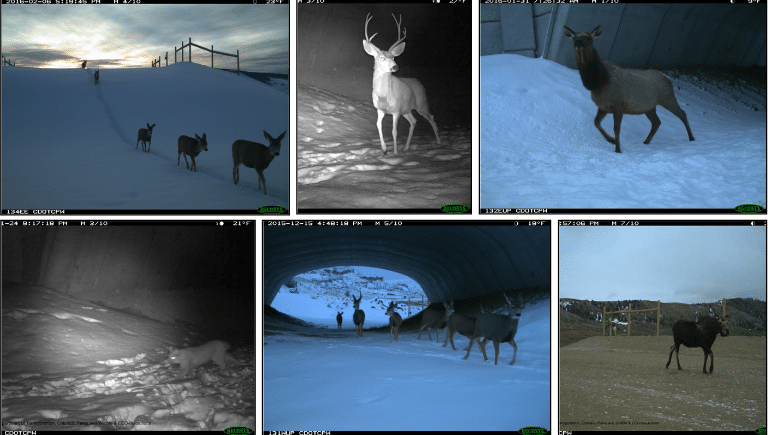

WYOMING: The Trapper’s Point project near Pinedale, Wyoming, which includes six underpasses and two overpasses, has become world-renowned for reducing pronghorn and mule deer collisions and for protecting the “path of the pronghorn” migration corridor.

FLORIDA: Florida has taken a proactive approach to protecting the endangered Florida panther, constructing over 60 wildlife crossings and installing accompanying fencing targeted at making it safer for panthers to cross the road. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, “Panther deaths caused by vehicle collisions have been sharply reduced in areas where crossings and fencing are in place.”

COLORADO: The Colorado Highway 9 Crossing Project with two overpasses and five underpasses has reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions by 87 percent in the first year. Success rate for mule deer has ranged from 82 percent in an underpass to 98 percent on an overpass.

But wildlife can’t be slackers–no one delivers to a nest or den.

- Turtles don’t have Tinder to find mates, they have to travel to breeding areas.

- Deer can’t use Doordash when they get hungry, they have to forage for food.

- Opossum don’t have Priceline to help them get away from predators.

- Armadillo can’t use Zillow to find a new home, they have to search for territory.

- Foxes can’t Facetime when they want to communicate with family, they have to find them.

To get what they need to survive and thrive, animals need to leave home and move around their habitat to meet their daily and lifetime needs. And too often that travel puts them in harm’s way.

On the Move

Wildlife move in daily, seasonal, annual, and lifetime cycles. Within a single day, they may only leave home to find food. Seasonally, wildlife move to adapt to changes in weather. And over the course of a lifetime, animals move extensively throughout their habitat for the many stages of life.

Some animals spend their entire life in a small area, while others may travel hundreds of miles a year. For example, an urban squirrel may find all the food, nesting material, and mates they need within a single city block. Alternatively, some pronghorn travel 300 miles roundtrip each year to follow available vegetation.

For wide ranging species like the pronghorn, getting from point A to point B and back often means having to navigate over several dangerous roads and highways. More than four million miles of concrete criss-cross the U.S. Our impressive infrastructure makes it easy for us to get around, but creates a deadly gauntlet for wildlife. In fact, an estimated 1-2 million large animals are killed by motorists every year; one animal every 26 seconds.

Wildlife Bridges

Not as easy as getting a Lyft, but innovative solutions for restoring wildlife movement have emerged over the last three decades. Wildlife biologists teamed up with highway engineers to design/build/create wildlife crossings to allow animals to cross over or under roadways, never having to enter the right-of-way. Wildlife crossings include bridges, enlarged culverts, and tunnels combined with fencing along roads to funnel animals to the crossings. These structures have proven to be the most effective measure to reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions. Some examples of successful wildlife crossing projects in the United States include:

WYOMING: The Trapper’s Point project near Pinedale, Wyoming, which includes six underpasses and two overpasses, has become world-renowned for reducing pronghorn and mule deer collisions and for protecting the “path of the pronghorn” migration corridor.

FLORIDA: Florida has taken a proactive approach to protecting the endangered Florida panther, constructing over 60 wildlife crossings and installing accompanying fencing targeted at making it safer for panthers to cross the road. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, “Panther deaths caused by vehicle collisions have been sharply reduced in areas where crossings and fencing are in place.”

COLORADO: The Colorado Highway 9 Crossing Project with two overpasses and five underpasses has reduced wildlife-vehicle collisions by 87 percent in the first year. Success rate for mule deer has ranged from 82 percent in an underpass to 98 percent on an overpass.

Great strides have been made but much more needs to be done. National Wildlife Federation is currently working with members of Congress to include funding for wildlife crossings in the upcoming surface transportation bill. With adequate funding, state transportation agencies can make wildlife crossings standard practice.

You can learn more about keeping wildlife on the move and next time you pick up your phone to order a curry in a hurry, be thankful that you don’t have to dodge highway traffic to get to your next meal!

This originally appeared on the National Wildlife Federation website.

0 comments on “For Wildlife, There’s No App for That”